Most people think of November 11 as Veterans Day. They’d be right. My brother, sister and I have an association with November 11 that runs deeper than our father’s short time in the army during World War II. Our mother was born on November 11. 1917, in Lodg, Poland.

Sylvia Gerson came to America in 1921 with her mother, brother and two sisters (a third would be born in New York). Technically an immigrant, she was as robust an American as any natural born citizen.

Perhaps even more so, as she was not constrained by then current American strictures that pigeonholed a woman’s role in society.

She had but a high school diploma but she became a full-charge bookkeeper, an anachronistic term often used to describe a woman of exceptional accounting talent who, for a variety of reasons, never earned the title of accountant, much less certified public accountant (Gilda’s mother, as well, was a full-charge bookkeeper).

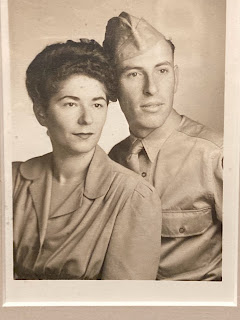

My parents married in 1942 barely two months after meeting. A mutual friend set them up. Perhaps the story’s apocryphal, but the way she sometimes told it, my father, Kopel, fell off a ladder in his store when he first saw her. It wasn’t from her good looks. Rather, it was her wild and frizzy hair.

They agreed, nevertheless, to go out that Friday night to a performance of either the Die Fledermaus or The Gypsy Baron, both comic operas (at various times she related both performances). When Kopel came to her family apartment he didn’t recognize her. She was all dolled up and beautiful. They were married six weeks later, Labor Day weekend 1942.

If six weeks seems like a whirlwind courtship, consider this. For several weeks they were apart because Sylvia went on vacation.

During one of their times together my mother garnered one of her favorite stories. Kopel took her back to an apartment he shared. Speaking Yiddish, his roommate asked if they would like to be alone, to which my father replied, also in Yiddish, “No, this one I am going to marry.” Unbeknownst to my father, Sylvia was fluent in Yiddish.

Their union was also a work partnership. As a full charge bookkeeper Sylvia ran the one-person office while Kopel ran the factory where they produced half-slips and panties sold mostly to chain stores across the country.

For a little more than four years Sylvia stayed home to raise their three children. I propelled her back to work with my poor eating and an exasperating habit of flinging peas off of my high chair tray. Today, peas are among my favorite vegetable.

Sylvia taught my brother and me to play ball. She made sure we went to Broadway shows and the opera. She took us to the Catskills. She enrolled us in private Hebrew schools and eight week sleepaway Jewish summer camps. She made our house the center of activity. Friday night poker games with my brother’s friends. Passover seders with as many as 40 participants. Overnight guests that prompted her to call our home Malon Forseter, malon being the Hebrew word for hotel. Her dinette table was never too full. Unexpected guests were met with the standard retort, “I’ll just add another cup of water to the soup.”

She was a self-taught cook. Her mother and older sister’s cooking skills were restricted to knowing they had entered a kitchen, which was not a place they sought to be in.

Mom, on the other hand, mastered cooking Jewish delicacies including matzo ball soup, kreplach, stuffed cabbage, sweet and sour lamb’s tongues and gefilte fish. I can still visualize her at our dinette table stitching together chicken necks stuffed with flour, bread crumbs or matzo meal, schmaltz (chicken fat) and fried onions. It’s called helzel, a dish that tasted better if one did not observe its preparation.

Though I wrote earlier that my poor eating sent her back to work, truth is Sylvia was a woman ahead of her time. Not just a homemaker and club woman—head of the PTA and active in temple and social groups—she also was an accomplished businesswoman not content or fulfilled in a stay-at-home mother role. Because of their business my parents could not always vacation together. My mother was confident and independent enough to travel to Israel and Europe by herself in the mid 1950s when she was just 40.

Sylvia instilled independence in her children. She trusted us to do our homework. We knew that trust came with a price—good grades.

Mom had a ribald sense of humor. If she saw you yawning she would say, “You wouldn’t be so tired if you slept at night instead of fooling around, but then sleep isn’t as much fun.”

On her night table at various times one could find a copy of “Lady Chatterly’s Lover” and “Tropic of Cancer,” risqué reading for the 1950s and 1960s.

These are memories from my youth. As she aged my mother’s joie de vivre deteriorated. She chain smoked. She was diabetic. She suffered bouts of congestive heart failure. A little dementia. She had one leg amputated below the knee because of her diabetes. A few years later on the eve of an amputation of her second leg she died of cardiac arrest.

My brother sister and I don’t dwell on the last decade or so of her life when she no longer was the vibrant source of our family life. It is enough to know that together with our father she molded us into the people we are today. And we are happy with the results.

One more thing worth noting. A few blogs ago I related how the number 11 has been significant in Gilda’s and my life together. It all started with my mother, born on November 11.